We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Date published : 30 July, 2024 Date last updated : 6 September, 2024 Download as a PDFNHS England publishes this guidance on behalf of the National Medical Examiner for England and Wales.

Following regulations laid in Parliament in April 2024, the Death Certification Reforms come into force on 9 September 2024 (see the end of this summary for details of the regulations). From this date, all deaths in England and Wales will be independently reviewed, either by a coroner where they have a duty to investigate, or by a medical examiner.

Standards for medical examiners are set by the National Medical Examiner for England and Wales, who is appointed by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This document, effective from 9 September 2024, sets out these standards, and provides guidance for implementing them and signposts to resources.

Medical examiners are senior doctors who, in the period before a death is registered (5 days), provide independent scrutiny of deaths in England and Wales not investigated by a coroner. Normally they work in this role in addition to their normal clinical duties, but will not have provided care for people whose deaths they review.

Medical examiners, supported by medical examiner officers, are based in local medical examiner offices. In England each medical examiner office has a lead medical examiner providing overall leadership to the office, and in Wales the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales has this role. In addition, NHS England employs regional medical examiners to provide regional leadership and guidance. Medical examiners address 3 key questions:

Their independent scrutiny has 3 elements. First, medical examiners or their officers give bereaved people the opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns. Second, they interact with the medical practitioner completing the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (MCCD). Finally, medical examiners carry out a proportionate review of medical records. If they detect issues or concerns, medical examiners refer cases for further review, but do not investigate themselves as their scrutiny must be completed rapidly.

As of June 2024, while operating on a non-statutory basis, medical examiners have independently scrutinised over 900,000 deaths in England and Wales, supporting bereaved people and providing the public with greater safeguards through improved and consistent scrutiny of non-coronial deaths. To ensure support is available when needed, the National Medical Examiner’s office made funding available to facilitate weekend and public holiday cover arrangements that meet the needs of local communities, including those where urgent release of bodies is a priority. There are already signs medical examiners are improving the consistency and appropriateness of referrals to coroners, and we expect their work will improve the quality and accuracy of recorded causes of death, benefitting analysis and research.

Improved support for bereaved people is a key feature of the medical examiner system. This together with the changes brought in by the Death Certification Reforms that affect other parts of the death management process – the work of attending practitioners, register offices, coroners and cremation services – should improve the experience of bereaved people, reducing the risk of unnecessary distress.

The relevant regulations are:

Throughout this document, “the regulations” refers to all the above. References to individual regulations are set out in full.

This document sets out the National Medical Examiner’s guidance and expected standards for medical examiners. It is issued under the National Medical Examiner (Additional Functions) Regulations 2024.

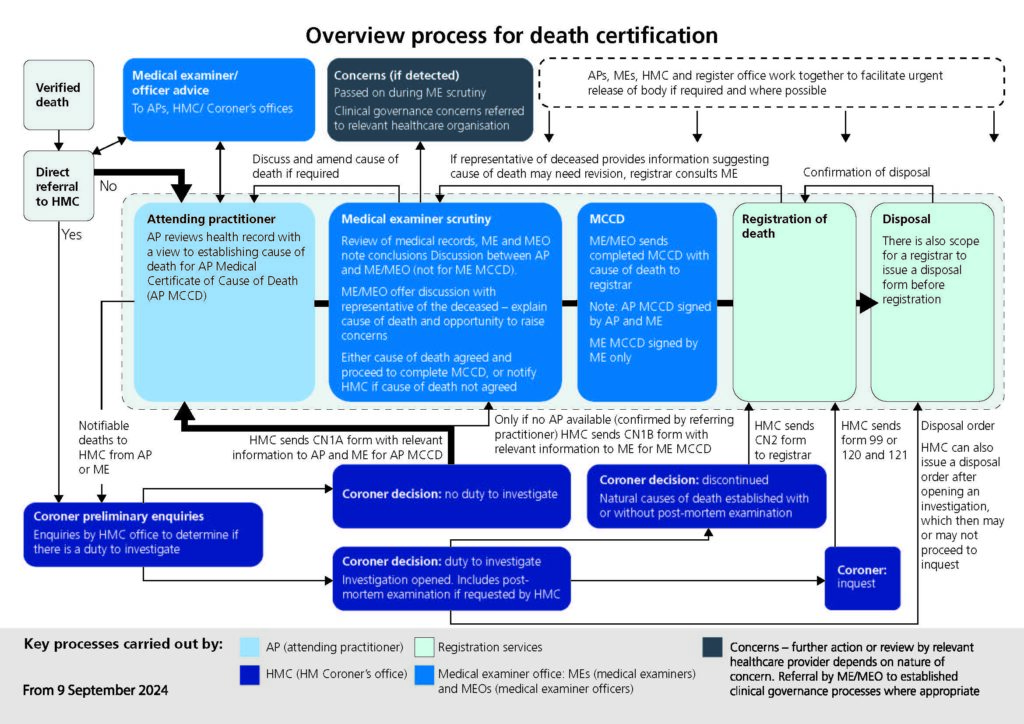

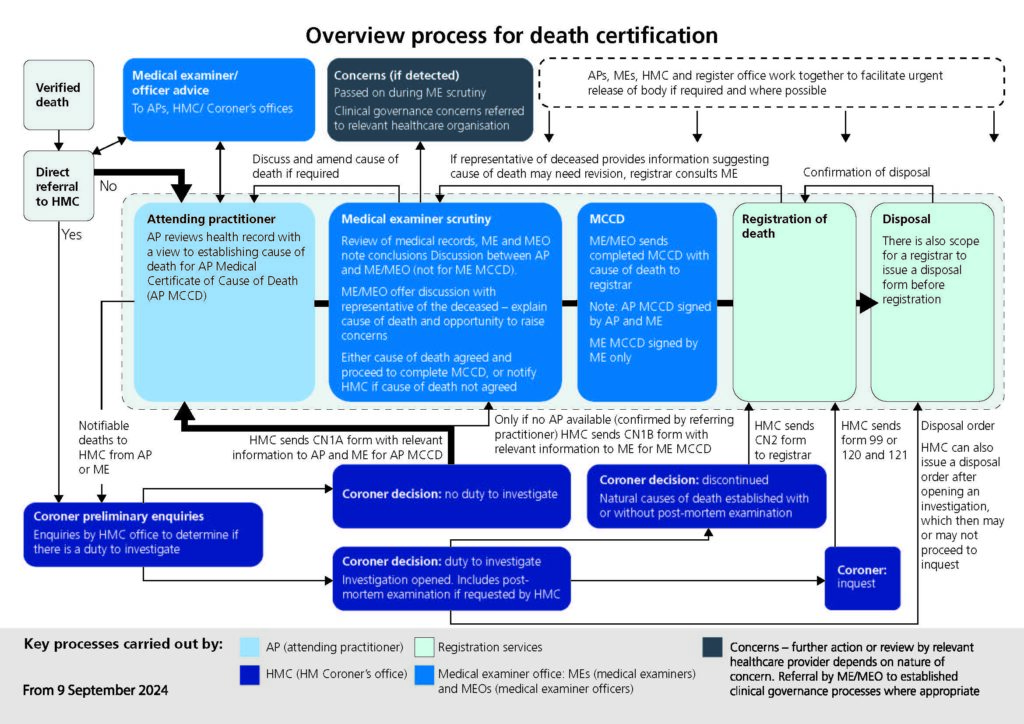

From 9 September 2024 all deaths that are not investigated by a coroner must be reviewed by NHS medical examiners. Government announced this change, which is part the new Death Certification Reforms, on 15 April 2024. A diagram that gives an overview of the new process can been seen below and is available for download.

Medical examiners are employed by NHS bodies in England and Wales and are supported by medical examiner officers. They support bereaved people by giving them a chance to ask questions and raise concerns with someone who was not directly involved in providing care to the deceased person during their lifetime. Medical examiners and officers help ensure Attending Practitioners’ Medical Certificates of Cause of Death (AP MCCDs) are completed consistently. Medical examiners have strengthened links between health services, coroner’s offices and register offices. They also provide an accessible expert resource for attending practitioners.

The medical examiner system has been designed to:

The National Medical Examiner (Additional Functions) Regulations 2024 allow the National Medical Examiner to issue guidance to English NHS bodies and Welsh NHS bodies setting out requirements for medical examiners’ qualifications, functions, and training. The National Medical Examiner must also publish standards of performance that medical examiners are expected to meet in exercising their functions. This document sets out those requirements and standards.

It should be noted that the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) publishes guidance for medical practitioners on completing Medical Certificates of Cause of Death and verification of death. The Ministry of Justice also publishes Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019 guidance for registered medical practitioners.

This guidance summarises key aspects of relevant legislation, but does not replace the need for medical examiners, their offices and their appointing bodies to know their statutory duties and detailed responsibilities as part of the death certification process, as set out in the relevant legislation.

Medical examiners, supported by medical examiner officers, review medical records and interact with attending practitioners and bereaved people to address 3 key questions:

The regulations require medical examiners to:

Medical examiner officers support medical examiners, but medical examiners remain accountable for fulfilling their statutory duties. Working with medical examiner officers, medical examiners should ensure the MCCD has been completed by an appropriately qualified attending medical practitioner.

Medical examiners are not responsible for verifying deaths or for confirming the identity of bodies. If there is reason to doubt the identity of a deceased person, medical examiners should make further enquiries with those responsible for caring for the deceased.

Section 19 of the Coroners and Justice Act defines the requirements for medical examiners: “A person may be appointed as a medical examiner if, at the time of the appointment, he or she:

a) is a registered medical practitioner and has been throughout the previous 5 years, and

b) practises as such or has done within the previous 5 years.”

Other clinicians cannot perform this statutory role. Medical examiners can be from all specialties and normally work as medical examiners for 1 or 2 sessions per week. Medical examiners who are appointed after retirement can continue to work as medical examiners for as long as they remain a registered medical practitioner with a licence to practise.

The National Medical Examiner recommends that medical examiners should be consultant grade doctors or other senior doctors from a range of specialties (including GPs) with an equivalent level of experience.

The Medical Examiners (England) Regulations 2024 and The Medical Examiners (Wales) Regulations 2024 set out the requirements for medical examiners’ terms and conditions. The Royal College of Pathologists has published a model job description.

Medical examiners must be appointed by NHS bodies in England and Wales, and are employed by NHS trusts in England and by NHS Wales Shared Services Partnership (NWSSP) in Wales. Further information for NHS bodies employing medical examiners is set out in Appendix 3. Other organisations or bodies cannot appoint people to carry out the statutory role of medical examiners.

Day-to-day management and oversight of medical examiners operates through local line management arrangements with the employing NHS body. The medical examiner role is classified as an additional responsibility. It either replaces a direct clinical care programmed activity or is an addition to this in an existing job plan, depending on what is manageable for the individual. The role must not be undertaken in SPA (supporting professional activities) time and NHS bodies should incorporate the medical examiner role into job plans for relevant medical practitioners.

Medical examiner duties must be covered in their whole practice appraisal. In both England and Wales, medical appraisal and revalidation for medical examiners will be governed by the usual General Medical Council (GMC) guidance. Appraisal will be undertaken by an appraiser approved by the relevant responsible officer. The Royal College of Pathologists has published information to support appraisal and revalidation of medical examiners.

The Medical Examiners (England) Regulations 2024 and The Medical Examiners (Wales) Regulations 2024 require that medical examiners complete appropriate training before starting in this role. This consists of 24 core e-learning modules that medical examiners must complete before starting medical examiner work; and face-to-face/virtual training provided by the Royal College of Pathologists that they must complete within 6 months of starting work.

Medical examiners who started work before 9 September 2024, and who had previously completed all compulsory training, only have to complete the 4 modules setting out the legal changes introduced by the death certification reforms:

They do not need to repeat the compulsory training they have already completed.

Medical examiners who started work before 9 September, but who have not yet attended the face-to-face/virtual training day, must do so as soon as possible, and no later than 6 months from 9 September 2024.

In addition to the 24 core modules, there are 61 other e-learning modules. Their completion is not a mandatory requirement but will help medical examiners in performing their role.

Once appointed, medical examiners should undertake continuing professional development (CPD) activities relevant to their role. Examples are completing further or updated e-learning modules, attending regional and national update meetings or further training sessions such as with local coroners. The National Medical Examiner’s good practice series published by the Royal College of Pathologists provides further insight. Reflective practice is also encouraged.

The Medical Examiners (England) Regulations 2024 and The Medical Examiners (Wales) Regulations 2024 set out requirements for the independence of medical examiners. In summary, medical examiners must not have provided care for the deceased person or be part of the team that provided care; they must not be related or closely related to the deceased person or to the attending practitioner or to any relevant medical practitioner, either personally or professionally; and they must not have a financial interest in the estate of the deceased person or have another other connection with them that could give rise to reasonable doubt about their objectivity.

Medical examiners must be able to exercise their professional judgement independently and be seen to do so, and the integrity of the medical examiner system must be protected. NHS bodies that employ medical examiners and officers must respect and support their independence. They should not prescribe budgets, ways of working or other matters that adversely affect the independent scrutiny provided by medical examiners or the operation of the medical examiner office.

NHS bodies that host medical examiner offices and those that may fund them, such as integrated care boards (ICBs) in England, must ensure that resources allocated for medical examiner offices are fully available. The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 s18A requires the Secretary of State to ensure NHS bodies in England appoint sufficient medical examiners and that the funds and other resources made available to medical examiners are adequate to enable them to discharge their functions. The Secretary of State has the power to direct NHS bodies regarding resources and the appointment of medical examiners.

There is more information on independence in section 4.

The AP MCCD requires a declaration from both an attending practitioner and a medical examiner that the causes of death are correct to the best of their knowledge and belief. Medical examiners’ training and experience of the medical and legal aspects of death certification should ensure that cases for which the medical examiner and attending practitioner cannot agree the cause of death are extremely rare. Where initial views differ, a pragmatic, constructive discussion usually facilitates agreement on cause of death and, where appropriate, the causes of death will be revised in the final completed MCCD.

In the rare case where a difference of opinion is irreconcilable, local escalation to the consultant in charge of the case for deaths in hospital) or discussion with another medical examiner who is a GP (for deaths in the community) and the lead medical examiner is recommended. If the issue still cannot be resolved, the coroner should be notified that the cause of death cannot be established. Medical examiners should make every effort to provide information and assistance to coroner’s offices in such cases.

Medical examiners carry out a proportionate review of medical records. They also interact with attending practitioners and bereaved people. Through these activities, medical examiners will sometimes detect concerns or issues with the care provided to the deceased person, either during their last illness or historically.

Medical examiners do not investigate concerns in depth. Instead they refer any concerns to established clinical governance processes for review. Section 5 sets out principles for referrals. Clinical governance reviews should not delay completion of the AP MCCD or registration of the death.

Medical examiners will ensure coroners are notified of deaths in line with Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019 guidance.

While medical examiners are always responsible and accountable for fulfilling their statutory functions, they are supported by medical examiner officers.

Medical examiner officers manage cases from initial notification through to completion and communication with the registrar. They are essential for the effective, efficient and consistent operation of the medical examiner system. Medical examiner officers provide a constant presence in the office, unlike medical examiners who usually work in the role part-time and come from a range of specialties.

Medical examiner officers support medical examiners by obtaining and carrying out a preliminary review of all relevant medical records (and additional details where required) to develop a case file setting out the circumstances of each death. This requires work with coroner’s offices, registrars, bereavement services, complaints managers and legal services. Over time, with experience and training, they can support medical examiners in determining causes of death and identifying the need for coroner notification.

Medical examiner officers are well-placed to identify patterns and trends, and to act as a source of expert guidance to all users of the medical examiner system.

Medical examiner officers can carry out the following tasks on behalf of medical examiners:

The medical examiner officer must keep a written record of all such interactions, and the medical examiner must review this before signing their declaration on AP MCCD or Medical Examiner Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (ME MCCD).

A medical examiner officer may or may not have a clinical background. They will:

The Royal College of Pathologists has published a model job description for medical examiner officers. In Wales, medical examiner officers are accountable to the Lead Medical Examiner Officer for Wales. In England, they will have a line manager within the NHS body that employs them. Where this line manager is not a medical examiner, medical examiner officers will be accountable to the lead medical examiner for operational matters. The employing NHS body and the line manager must respect and support the requirement for medical examiners and medical examiner officers to support independent scrutiny. NHS bodies employing medical examiners and officers must not request or require them to carry out other work that conflicts with statutory medical examiner duties or inhibits fulfilment of those duties.

Some NHS trusts have considered combining medical examiner officer duties with other roles. This is not supported. Resources are provided to NHS bodies on the basis that they facilitate medical examiner activity, and operational arrangements at NHS bodies employing medical examiners must support their independent role. Medical examiners have a specific legal basis for accessing records of deceased persons that does not apply to NHS staff carrying out other duties such as for bereavement or mortuary services. Joint roles blur lines of accountability and make it more difficult to provide assurance on each of the above points.

There is no statutory requirement for training of medical examiner officers. However, it is advised that they should complete the 26 core e-learning sessions and face-to-face/virtual training provided by the Royal College of Pathologists. Medical examiner officers will benefit from on-the-job training, such as through constructive case discussion with medical examiners, as well as appropriate CPD activity.

Medical examiners, their offices and their appointing body must adhere to the statutory duties set out in the Medical Examiners (England) Regulations 2024, the Medical Examiners (Wales) Regulations 2024 and the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024, and the principles set out in this section.

The independent scrutiny carried out by medical examiners must comprise:

A core objective of the medical examiner system is to support bereaved people, and all operational and strategic decisions should be considered from this perspective. Medical examiners and officers need to interact compassionately and sensitively with bereaved people, and be aware that heightened emotions in those who are grieving may affect how they behave and respond. They need to communicate sensitive information with tact and sensitivity, appreciating its potential impact, avoiding jargon and explaining technical or clinical terms in ways non-clinicians will understand.

Bereaved people will need an environment that enables them to express their concerns, where they can be confident their worries or feelings are respected and seen as important.

Bereaved people will at times raise concerns that require action such as referral to the clinical team responsible for care and/or to healthcare providers’ complaints services. Such referrals should be made in accordance with good practice and local complaints policies. Section 5 gives further detail on referring concerns and themes.

Some deceased people may have no relatives. Medical examiners and officers may then be required to engage with a representative of the deceased or a person acting in the absence of next of kin.

The Medical Examiners (England) Regulations 2024 and The Medical Examiners (Wales) Regulations 2024 set out circumstances where medical examiners are deemed to be insufficiently independent. When medical examiners become aware that these circumstances apply, they must not carry out medical examiner statutory functions (or must cease doing so where they become aware after starting scrutiny) and must notify their appointing body such circumstances apply.

However, beyond these prescribed circumstances, it remains important that medical examiners are not encumbered by other roles or personal connections that could be perceived to influence their clinical judgement or independence.

Medical examiners must maintain the integrity of the medical examiner system and demonstrably be seen to do so. Providing independent scrutiny of causes of death, as summarised in section 2, is a statutory responsibility. Medical examiners should also consider other factors that could affect their ability to provide independent scrutiny or reasonably cause bereaved people and others to doubt they are able to do so.

It is not possible to provide an exhaustive list of the positions it would be unacceptable for a medical examiner to hold. However, being the overall trust or health board mortality lead or a member of the executive team or board of the NHS body that employs medical examiners would not be acceptable. Medical examiners must carefully consider whether any position or office they hold could reasonably be judged to conflict with their duty to provide independent scrutiny of deaths and their responsibility to reach objective decisions about whether to escalate matters such as trends and concerns about care.

Depending on their medical specialty, medical examiners may need to adapt their working practices. For example, those who are practising pathologists should not conduct a post-mortem examination requested by a coroner if they had notified the death to the coroner. While it is acceptable for someone who is a medical examiner to be an expert witness in relation to their medical specialty, they should not act in their capacity as a medical examiner as expert witnesses in inquests or be paid for providing a medical opinion. Having a medicolegal practice and being a medical examiner represents a potential conflict of interest and should be declared through the employing NHS body’s procedures. Medical examiners with a medicolegal practice should not accept a medicolegal instruction in a case they have scrutinised or where they have a connection with the medical examiner who has.

These examples are not exhaustive, but illustrate the principles expected by the National Medical Examiner, and that medical examiners must be vigilant to avoid conflicts of interest and consider how best to maintain public confidence in the medical examiner system.

Bereaved people may ask to see the medical examiner’s record of their scrutiny. The National Medical Examiner favours an assumption of transparency and openness to empower bereaved families. When a bereaved person who spoke with the medical examiner office about causes of death makes a reasonable request to see records of medical examiner scrutiny, these records should be shared where possible. However, medical examiner offices must adhere to statutory requirements and should follow the relevant employing NHS body’s policies and procedures to avoid inappropriate sharing of confidential information. If the medical examiner office uses a local NHS IT system to store their records of scrutiny, its use is likely to be governed by the employing NHS body’s policies and procedures.

Each NHS body in England that has a medical examiner office must appoint a lead medical examiner to provide leadership on operational arrangements and escalation of concerns. In Wales, this role is fulfilled by the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales. As with all medical examiners, lead medical examiners must not be a member of the executive leadership of the employing NHS body.

Employing bodies must facilitate and respect independent scrutiny by medical examiners, and should enable medical examiners to share information about trends and concerns (without identifiable personal information) with lead medical examiners and regional medical examiners in England, and in Wales with the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales.

The GMC publishes ethical guidance for all medical practitioners who detect issues with the quality of care. For example, Working with colleagues notes that medical practitioners must respect the skills and contributions of others, and must treat colleagues fairly and with respect. All medical practitioners must adhere to the GMC Good medical practice and to applicable information governance law and policies. It is not anticipated that such requirements will impede medical examiners passing on feedback and referring concerns as appropriate, but if in doubt in a given case, advice should be sought (for example, from the appointing NHS body’s Caldicott Guardian) where appropriate.

This section provides principles for medical examiners to consider when deciding to whom they should refer concerns and share feedback. Medical examiners should exercise professional judgement in applying these principles to each case, and must consider all relevant persons and organisations that may benefit through referral of concerns. They should maximise the opportunities for learning and to improve care, and adapt to practices and requirements that change over time. When referring concerns, medical examiners need to exercise judgement and act proportionately, ensuring the responsible healthcare provider can take appropriate action with the protection of future patients in mind, while interacting with colleagues respectfully.

In most cases where medical examiners refer concerns to another person or organisation, it will be courteous and appropriate to inform the treating medical practitioner of the referral. In a few cases (for example, suspected criminal activity by the medical practitioner or clinician) it is not appropriate to inform them. If in doubt, advice should be sought from the lead medical examiner, Lead Medical Examiner for Wales or regional medical examiner in England.

While the legal requirements for providing information to other healthcare providers about trends and patterns are different from those for referring concerns about individual cases with identifiable and/or confidential information, the common principle is that medical examiners will identify opportunities to improve care and take appropriate action.

Medical examiners review all deaths not investigated by coroners, and in the vast majority there will be no concerns about care. Indeed, bereaved people often provide positive feedback about the patient’s care before death and want this to be passed on to frontline staff. Medical examiners should ensure bereaved people are happy for their feedback to be shared or are made aware that it will be included in the general information disseminated by the medical examiner office as part of the process. In England, the Learn from Patient Safety Events service (LFPSE) can also capture ‘good care’ events and the provider delivering the service can see those that are.

However, in a minority of cases there will be concerns about care. Medical examiners must still facilitate registration of the death in a timely manner and will not investigate concerns in depth. Rather, when they detect concerns about care, their role is to refer these to the appropriate quality lead at the relevant organisation, ensuring this person is of sufficient seniority to ensure appropriate action is taken. Medical examiners should follow local and national requirements, and the following general principles should be followed for appropriate referral of concerns.

Medical examiners must also consider whether individual circumstances merit informing persons additional to those listed above. For example, where similar concerns have been notified previously but continue to occur, or there is reason to believe those notified or responsible for reviews may have a personal or professional interest in the outcome. The concerns and views of bereaved people must be considered and, as far as is reasonably possible, reflected in the action taken. At all times, medical examiners will also need to consider whether the coroner needs to be notified of the death.

Once the medical examiner has referred the concern to the appropriate healthcare organisation, it is the responsibility of that individual or healthcare organisation to determine the appropriate review process, to carry this out and to take appropriate action.

In the majority of cases, concerns can be shared with the healthcare organisation without any issue. It will already be aware of the deceased’s confidential health and care information, and sharing concerns is in the public interest and within people’s reasonable expectations as to how their information will be used. Matters may be more complex when sharing confidential information with ICBs in England as these do not hold patient information. If there is any doubt about the basis for sharing confidential information, advice should be sought from local information governance teams.

There are 3 further considerations. First, the National Medical Examiner encourages a constructive and developmental approach that respects the professional status of clinical colleagues, and informing treating practitioners or teams of any concerns about care in addition to formal reporting.

Second, there may be feedback about issues that do not amount to a concern about care, but action around them could improve the experience of patients or bereaved people in future. A common example is communication that could have been better, and were it improved future misunderstandings and complaints could be reduced. It is usually appropriate to inform the attending medical practitioner or treating team of such feedback.

Third, medical examiners must remain vigilant for extremely rare but serious cases where there may be reason to suspect professional misconduct or criminal activity or intent. Referral to a coroner and/or the police will be appropriate in some cases. Where there is reason to suspect criminal activity or intent, the police and relevant regulatory authorities must be informed. Medical examiners should follow GMC guidance and other appropriate information. If in doubt, advice should be sought from the lead medical examiner, Lead Medical Examiner for Wales or regional medical examiner in England..

Medical examiners in England are encouraged to refer to the Patient safety incident response framework (PSIRF), which sets out the approach to develop and maintain systems and processes for responding to patient safety incidents, for the purpose of learning and improving patient safety. Policy guidance on recording patient safety events and levels of harm for users of LFPSE defines levels of harm and provides guidance on the appropriate categories when recording incidents. In Wales medical examiners should be familiar with the Patient safety incident reporting and management policy and NHS Wales complaints and concerns process for raising complaints: Putting things right. While medical examiners are not responsible for recording incidents, they should refer colleagues to this information where appropriate.

Medical examiners should support the national reporting frameworks provided by the NHS and other partners by staying up to date with the National Medical Examiner’s good practice papers published by the Royal College of Pathologists, and alerting attending practitioners and other clinical colleagues to national initiatives. Responsibility for reporting individual cases remains with the lead clinicians.

Where equipment failure or design issues contribute to, cause or could have caused death, medical examiners in England should ensure that a patient safety incident is reported, in addition to coroner notification where appropriate. Other relevant guidance includes Learning from deaths in England, the Mortality Review Programme in Wales and the PSIRF. In addition, it may be appropriate to report a problem with a medicine or medical device.

Medical examiners may identify issues that invoke the duty of candour (UK Government) or duty of candour (Welsh Government), a duty that is intended to ensure providers are open and transparent with service users. It sets specific requirements that providers must follow when things go wrong with care and treatment, including informing people about the incident, providing reasonable support and truthful information, and apologising. The duty of candour continues to apply to the provider and treating team that provided the care; it does not transfer to the medical examiner.

There are additional requirements for deaths of children (up to age 18 and including neonates). In England, the statutory child death review process must be followed, and concerns should be notified to the child death review co-ordinator. In Wales it is appropriate to inform the health board medical director and/or relevant assistant medical director, and the Child Death Review Programme. Medical examiners should refer to the National Medical Examiner’s good practice paper.

For more details go to section 7.

Medical examiners have important links to established clinical governance processes, highlighting cases for them to review and ensuring concerns are flagged to the relevant trust or health board mortality lead and/or clinical quality lead in community providers or ICBs in England. Medical examiner offices should work with healthcare providers, including GP practices, and with ICBs in England and health boards and trusts in Wales to agree referral processes that align with local arrangements.

Medical examiners will need to adapt to local clinical governance arrangements. For example, many healthcare providers and organisations appoint governance leads who are responsible for collating information and responding to identified issues. Medical examiners should ensure they understand and agree referral arrangements with local stakeholders, and that action taken by medical examiner offices is proportionate. Medical examiner offices that receive referrals from independent healthcare providers will need to agree appropriate referral actions with them.

However, medical examiners should not be involved in mortality reviews of cases they independently scrutinised or undertake mortality review work in medical examiner time. The need to preserve independence makes it inappropriate for a medical examiner to be the overall trust or health board mortality lead.

Often healthcare providers are not informed of the deaths of patients they may have treated in the past. This can represent a missed opportunity for learning and improvement for those providers that were not caring for the patient at or immediately before their death. For example, a patient may have been treated by a provider of mental health care services or independent healthcare provider during a previous illness, but these providers may not be informed of their death. Medical examiner offices should facilitate learning where possible but will need to take information governance requirements including confidentiality into account.

Causes of death for individuals are publicly available, and medical examiner officers can and should share these with other healthcare providers that previously provided care for the deceased and would benefit from having this information. Where a concern with previous care is detected, confidential information can be shared with the provider to enable learning. Concerns about care should be shared in a proportionate manner. Medical examiners can also share anonymised information.

Medical examiners should share themes, repeating issues and patterns such as clusters of cases displaying similar characteristics to inform learning and improvement. Medical examiner offices should respond positively to reasonable requests for data and intelligence regarding such trends from individuals or bodies who would reasonably be expected to request such information. Medical examiners should only decline where the information is available through other sources, or providing it would impose an unreasonable administrative burden on the office. Information governance requirements mean some types of information cannot be shared, but data such as patterns and trends will usually be aggregated or anonymised to enable dissemination without any information governance issues arising.

Medical examiner offices should share anonymised trends or patterns of concern regarding a locality or a healthcare provider with the relevant regional medical examiner in England or Lead Medical Examiner for Wales, to facilitate prompt consideration, investigation and action. As appropriate, the regional medical examiner in England or Lead Medical Examiner for Wales will share such information with the National Medical Examiner, and in England with the relevant NHS England regional medical director or in Wales with the relevant health board medical director or the Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Wales, who has responsibility for patient safety.

Where medical examiners detect and refer concerns regarding the quality of healthcare, the provider of those services can be expected to take action to resolve them. However, medical examiners may consider that further escalation is required where the same issues continue to be identified or do not appear to have been resolved.

In these cases, medical examiners in England should escalate concerns to lead medical examiners in the first instance. Lead medical examiners in England may escalate matters to the regional medical examiner (employed by NHS England) as may other medical examiners if necessary. In addition, lead medical examiners (and other medical examiners) may inform the ICB where appropriate. In Wales, medical examiners should inform the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales.

The regional medical examiner in England/Lead Medical Examiner for Wales and the medical director (or equivalent) of the relevant healthcare provider should together agree and implement solutions where appropriate. In England the regional medical examiner will work with the relevant NHS England regional medical director and their teams to support NHS providers to take appropriate action. In Wales concerns should be escalated to the health board medical director or the Deputy Chief Medical Officer for Wales who has responsibility for patient safety, as appropriate.

Regional medical examiners in England and the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales are accountable to the National Medical Examiner, and they will escalate concerns to the National Medical Examiner if required.

Coroner notification is required in the circumstances set out in the Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019. Medical examiners should clarify with attending practitioners who is best placed to notify the coroner. It can be helpful for the medical examiner office to take the lead but this should not be assumed, and often attending practitioners will make referrals, in some cases without involvement of the medical examiner office (for example, when the requirement for notification is clear).

Medical examiner offices must be open at times that meet the needs of the local population, with cover provided for staff on leave. There should be a system for prioritising cases that require urgent attention, while maintaining the integrity of the medical examiner system.

Most medical examiners’ work can be undertaken during normal office hours. Cover for weekends and public holidays is likely to be required in most areas, though a continuous ‘on call’ service is not necessary. Arrangements at each office should reflect local health priorities and the needs of communities, particularly if there is regular demand for urgent release of bodies at weekends and public holidays. Urgent release may be required to facilitate organ and tissue donation, or to fulfil religious practices and other needs of local communities. The National Medical Examiner’s series of good practice papers includes weekend and public holiday cover and urgent release of a body.

For flexible and sustainable provision of cover, NHS bodies may consider arrangements between medical examiner offices. Regional medical examiners in England and the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales can facilitate discussions between NHS bodies.

NHS bodies that employ medical examiners should have contingency or business resilience plans to ensure the availability of adequate service to support death certification during, for example, emergency situations that result in a sudden increase in the death rate or disrupt normal ways of working.

Medical examiners and officers should demonstrate the highest professional standards at all times. They should make every effort to deliver timely, efficient and effective services.

Medical examiners and officers should collaborate with neighbouring medical examiner offices, sharing experiences and expertise to support peer learning. Regional medical examiners in England and the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales work with medical examiner offices to facilitate this.

Medical examiner offices need to maintain good working relationships with the local coroner, registration services and other stakeholders, such as faith groups and funeral directors.

In most cases, the medical examiner office that should provide independent scrutiny will be clear. However, there will be a small minority of cases where more than one office could potentially provide scrutiny; for example, where the deceased person was cared for through virtual wards or transferred between providers during their final illness. Medical examiner offices must work constructively with each other to agree arrangements in such cases and a pragmatic approach is recommended.

Above all, the interests of bereaved people must be considered. Other considerations may include where the most efficient arrangements exist for sharing relevant records of the deceased person, which register office will register the death, and whether coroner notification is likely and if so the relevant coroner’s office. Regional medical examiners in England and the Lead Medical Examiner for Wales can assist if cases cannot be resolved, but the National Medical Examiner expects arrangements for all but exceptional cases to be agreed locally.

It is helpful to have medical examiners from a range of medical specialties, including GPs, to provide a breadth of clinical experience and expertise. Medical examiners can and should review deaths following treatment by any speciality. If helpful, they can seek advice from other medical examiners with more knowledge of particular areas of care or from other colleagues who are not part of the team that provided care to the patient; for example mental health specialists, including psychiatrists and those working with patients with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Informants are required to register deaths within 5 days of the register office receiving the completed AP MCCD or ME MCCD from the medical examiner office. Delays in all parts of the death certification process must be kept to a minimum, including the work of medical examiners, but medical examiners must devote adequate time to each case to maintain the integrity of independent scrutiny. Medical examiner offices should record delays beyond their control, such as those resulting from delayed submission of medical records from the attending practitioner or other healthcare providers.

Scrutiny of straightforward cases should normally be completed within 24 hours of the medical examiner office being notified of the death. Medical examiners must prioritise case scrutiny appropriately and respect the needs and wishes of bereaved people, including where urgent release of a body is required.

The smooth operation of death certification and registration relies on the accurate and timely completion of documentation. All healthcare providers in England and Wales need effective and efficient processes to notify medical examiners of deaths and provide records.

The Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024 require medical examiners to record any conclusions they have drawn from their enquiries and they should record these accurately and objectively. Medical examiners should also carefully record the scrutiny they have undertaken: interactions, the available information, the actions taken and the reasoning behind decisions. They should be conscious that records may be seen by other parties and need to be drafted in a manner that will not cause unnecessary distress and is understandable to future readers. It is possible that inquiries in future years will request medical examiner records. While medical examiner records are unlikely to be considered to be health records as defined by the Access to Health Records Act 1990, there is useful GMC guidance.

The work of the medical examiner office should be subject to appropriate audit processes, in line with national guidelines. Good documentation will also provide medical examiners with material to satisfy medical revalidation requirements in relation to their medical examiner role. The current expectation is that records of scrutiny will be retained for 15 years.

The National Medical Examiner requires medical examiner offices in England to submit information about activity and significant findings on a quarterly basis. The National Medical Examiner will agree the reporting requirements in Wales with the Welsh Government and NWSSP. Details are communicated separately and may change over time.

Medical examiner officers help keep processes flexible and efficient by supporting medical examiners and carrying out certain tasks on their behalf. However, the medical examiner remains personally responsible and accountable for ensuring that all components of scrutiny are carried out, for all decisions and for ensuring that concerns are assessed and escalated where necessary. Medical examiner officers can carry out 2 of the 3 components of scrutiny on behalf of the medical examiner (see also section 3):

While the medical examiner officer may prepare the records for review, they cannot review records on the medical examiner’s behalf. The medical examiner must review the medical record.

The Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024allow medical examiners to undertake an external examination of the deceased person or ask another individual to do so on their behalf. The National Medical Examiner expects that viewing bodies during medical examiner scrutiny will happen rarely and by exception. In the rare circumstances where a medical examiner decides examination of the body is required and asks another person to carry this out, they must satisfy themselves that this person is not related to the deceased. The Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019 set clear criteria for coroner referrals, and for other cases medical examiner scrutiny must remain proportionate.

In the few cases where a medical examiner has not detected grounds for notifying the coroner, but where inspection of the body may have some benefit, normal practice would be to ask an anatomical pathology technologist (in trusts and health boards) or funeral director (in the community) to carry out an external inspection. An example could be following a stroke where the cause of death appears entirely natural, but medical records mention odd marking to a limb. For peace of mind, a medical examiner might request that the marking is viewed. The findings of any inspection and action taken or not taken must be recorded in the record of scrutiny.

The attending practitioner should develop their own preliminary view of the cause of death before discussing the case with the medical examiner or medical examiner officer. It is not the role of medical examiners to tell the attending practitioner what causes of death to record. The attending practitioner remains personally accountable and responsible for completing their statutory statement confirming the causes of death.

There is official guidance for completing a MCCD. Completing the AP MCCD requires a medical examiner to make a statutory declaration confirming the causes of death. As medical examiners generally spend most their time in other clinical roles, and records and other information may arrive at different times, there will be cases where an AP MCCD is ready to be finalised and sent to the registrar, but the medical examiner who carried out the scrutiny (or part of scrutiny) is not available to sign the declaration and another medical examiner will need to take over the case. This scenario is akin to clinical handover.

If another medical examiner takes over the case, the standard of scrutiny and the medical examiner statutory duties and accountability are the same. The new medical examiner must make the enquiries they consider necessary and draw conclusions from their enquiries and other information they consider relevant before signing the declaration. They will benefit from reviewing the original medical examiner’s summary and conclusion, as these are likely to help them complete scrutiny faster by avoiding unnecessary repetition. The new medical examiner can also rely on records of tasks undertaken by medical examiner officers on behalf of the original medical examiner. These together will enable the new medical examiner to complete the MCCD more rapidly.

Arrangements for ME MCCDs are explained in section 7.

From 9 September 2024, the Access to Health Records Act 1990 gives medical examiners a specific statutory right of access to records of deceased patients that they consider relevant when carrying out their duties. The Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024 require medical examiners to make whatever enquiries appear to be necessary to confirm or establish the cause of death. If records of a deceased patient are not made available and the medical examiner is unable to establish the cause of death, they are obliged to notify the death to the coroner. Further information about the legal basis for medical examiners’ access to records and a template statement for use by medical examiner offices are provided in Appendix 2.

Medical examiner offices and healthcare providers have established a range of methods for sharing patient records. It should be noted that some mechanisms for sharing electronic patient records are designed to be used by staff providing direct care to the patient, and their use may be restricted to this purpose by data sharing agreements. Healthcare providers should consider whether their data sharing arrangements support medical examiner requirements appropriately, and ensure electronic patient records are shared rapidly with medical examiners to avoid unnecessary distress and delay to bereaved people.

In some neonatal cases, medical examiners may consider that the maternal patient records are relevant. Unless the mother is also deceased and her death is undergoing scrutiny by the same medical examiner, the specific right of access to these records under the Access to Health Records Act 1990 would not apply. If this is not the case, the usual information governance principles for living patients would apply to access to the maternal patient record (for example, obtaining consent from the mother or establishing another legal basis).

Government introduced the medical examiner role as an important safeguarding measure, and the requirement for independent scrutiny of all deaths in England and Wales cannot be overridden. All deaths must be reviewed by a medical examiner unless the death is being investigated by a coroner or has been notified to a coroner and the coroner has yet to decide whether they have a duty to investigate.

It is highly unlikely but feasible that a patient could indicate before death that they do not wish a medical examiner to provide independent scrutiny or to access their medical records. In these circumstances the right of access under the Access to Health Records Act 1990 may not apply. The Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024 require attending practitioners to respond to those enquires. If a patient expressed a wish that medical examiners do not review their records after death, this does not alter the duty placed on them to review relevant patient records to establish causes of death. This mitigates the risk of vulnerable individuals being influenced by family members or staff and ensures all deaths will be reviewed independently.

Similarly, a patient in life may express a wish (with capacity) that some or all information about their health is not shared with family members after death. Medical examiners should respect such wishes insofar as this does not conflict with their duty to explain causes of death to a bereaved person and to offer them an opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns. Medical examiners will need to share with the bereaved person the information from the deceased person’s health history as required to fulfil their statutory duties and exercise professional judgement in deciding what is appropriate to share. It should be noted that causes of death are a matter of public record.

If a member of the public has a complaint about a medical examiner or officer in England, they should make this to the NHS trust or NHS foundation trust where the medical examiner or officer is employed, or the ICB that commissions services from the NHS trust or NHS foundation trust. English NHS complaints regulations would apply. In Wales, complaints about the medical examiner service should be referred to the NWSSP complaints process. Complainants can also contact the complaints team in the relevant health board or trust, and Welsh NHS complaints regulations apply.

If a complaint is made to an NHS trust employing medical examiners in England, the trust should follow its usual complaints process. The National Medical Examiner requires medical examiner offices in England to inform the regional medical examiner each quarter about the complaints they receive.

If a complaint is made to an ICB in England, the ICB should follow its usual complaints process, and in addition must inform NHS England’s regional medical examiner of the complaint and consult them before finalising the response. The ICB should follow its usual procedure for seeking consent before sharing the complaint with the NHS trust and the regional medical examiner.

Ultimately, if complainants are dissatisfied with responses, they can contact the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman in England or the Public Services Ombudsman for Wales. It should be noted that, although medical examiners are employed by NHS bodies, under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 Section 19(5) NHS bodies do not have “any role in relation to the way in which medical examiners exercise their professional judgement as medical practitioners”.

Medical examiner offices and NHS bodies employing medical examiners should note that the work of medical examiners is not exempt from Freedom of Information (FOI) requests, other than where the usual FOI exemptions apply. Local FOI teams will be able to provide further advice.

Similarly, data protection legislation also applies to the processing of personal data by medical examiner offices (that is, information about identified or identifiable living people). While the work of medical examiners relates principally to deceased individuals, medical examiner offices also hold personal data relating to some living people, for example next of kin recorded in the health record. NHS bodies employing medical examiners are data controllers for the purposes of data protection legislation and are therefore responsible for complying with individuals’ requests to exercise their data protection rights.

Individuals have a right to make a subject access request for copies of their personal data (and other supplementary information about why and how their personal data is processed), subject to exemptions under the data protection legislation.

Records of medical examiner scrutiny are not health records. ‘Health record’ is a defined term under the Data Protection Act 2018 and the Access to Health Records Act 1990: “A health record:

(a) consists of information relating to the physical or mental health of an individual who can be identified from that information, or from that and other information in the possession of the holder of the record; and

(b) has been made by or on behalf of a health professional in connection with the care of that individual.”

Access to medical examiner records of scrutiny should be managed by the medical examiner office, in line with the relevant NHS body’s data retention and other policies.

Medical examiners should ensure the information held by their indemnity provider is up to date. NHS indemnity will apply as medical examiners must be employed by an NHS body. When medical examiner system implementation started, NHS England confirmed with NHS Resolution that NHS bodies employing medical examiners (and medical examiners employed by NHS bodies) will be covered for legal liabilities arising from their medical examiner activity through membership of the Liabilities to Third Parties Scheme (LTPS).

NWSSP is a member of the Welsh Risk Pooling Scheme, which has confirmed that NHS bodies employing medical examiners (and medical examiners employed by NHS bodies) in Wales will be covered for legal liabilities arising from their medical examiner activity through NHS health bodies’ membership of the Welsh Risk Pooling Scheme.

All medical examiners are strongly encouraged to hold ‘top up’ cover from a suitable defence organisation to assist in the event of criminal or regulatory investigations or actions brought against them.

Effective partnership working between all parts of the death certification and management process improves the experience for bereaved people. Completion of the AP MCCD after medical examiner scrutiny increases consistency and supports rapid registration of the death. Medical examiners support consistent notification of appropriate deaths to the coroner.

The Ministry of Justice provides guidance about cremation forms and crematorium medical referees.

The Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019 set out the types of deaths that medical practitioners must notify to senior coroners and these override any local guidance. Medical examiner offices are encouraged to work with coroner’s offices to ensure that local ways of working are efficient and provide the best possible service to bereaved people.

Where a death is notifiable to the a coroner, medical practitioners including medical examiners should make the notification as soon as practicable, and they should send relevant information in writing. The detail in this should be as full and informative as possible. While in many cases the attending practitioner will make the notification, coroners will often value the medical examiner’s thoughts on a case if they have provided any scrutiny. However, it is not appropriate to expect medical examiners to review every case before it is notified to the coroner.

A benefit of the medical examiner role is that notification of appropriate cases to coroners becomes more consistent. Where a death has been notified to the coroner, they will decide whether they have a duty to investigate the death. If they decide their duty to investigate is not engaged, the coroner will send form CN1A to the attending practitioner and the medical examiner office. This should be accompanied by relevant information to enable the attending practitioner and medical examiner to establish the cause of death and complete the AP MCCD. Medical examiners should not complete their statutory declaration unless they are satisfied they have reviewed all the information necessary to confirm causes of death.

Medical examiners support registrars by providing greater consistency in and quality of AP MCCDs. Medical examiner offices and register offices are encouraged to work together to ensure that local ways of working are efficient and provide the best possible service to bereaved people. This is also supported by the Cause of Death List.

Medical examiner offices and register offices need to agree processes to enable the best possible experience for bereaved people. Clarity about the following will assist with this:

Where an informant provides a registrar with information that leads them to believe that the cause of death stated on the AP MCCD may need to be revised, the registrar must consult a medical examiner. This may happen, for example, where the informant is not the person who spoke with the medical examiner or officer. In these cases medical examiners should consider if the information is new, and if so, whether the causes of death require amendment. Registrars are no longer expected to refer deaths to coroners, actions under the new process are set out in section 8.

It is a statutory requirement for an attending practitioner to complete the AP MCCD. The GMC sets out this obligation, confirming this is part of medical practitioners’ professional responsibility to their patients.

“Your professional responsibility does not come to an end when a patient dies. For the patient’s family and others close to them, their memories of the death, and of the person who has died, may be affected by the way in which you behave at this very difficult time… You must be professional and compassionate when confirming and pronouncing death and must follow the law, and statutory codes of practice, governing completion of death and cremation certificates. If it is your responsibility to sign a death or cremation certificate, you should do so without unnecessary delay.” (GMC, Treatment and care towards the end of life guidance, paragraphs 83-85)

The 2024 death certification reforms widen the pool of medical practitioners who can complete AP MCCDs, as the requirement to have seen the patient in the 28 days before death or to see the body after death has been withdrawn. The only requirement is that the medical practitioner must have attended the deceased in their lifetime. This will enable more AP MCCDs to be completed in the normal way and scrutinised by a medical examiner. Such deaths can then be registered without unnecessary referral to a coroner, avoiding unnecessary delays for bereaved people.

There will be a small minority of cases where the cause of death is known and natural but no medical practitioner who attended the deceased can be identified within a reasonable period. Historically, there were limited arrangements for such circumstances, and even where the cause of death was a known, the death had to be notified to the coroner and registered as uncertified.

The Coroners and Justice Act 2009 allows for completion of a ME MCCD in exceptional circumstances where:

This process allows the death to be registered as certified and avoids unnecessary post-mortem examinations and uncertified deaths where the cause of death is known, thereby minimising delays and distress for bereaved people.

When medical examiners complete a ME MCCD, other than not interacting with an attending practitioner, all elements of medical examiner scrutiny remain in place; that is, supported by medical examiner officers, they will offer bereaved people the opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns, and they will carry out a proportionate review of medical records. In circumstances where the medical examiner concludes that they are unable to establish the cause of death, the case can be referred back to the senior coroner.

An ME MCCD will only be completed in the exceptional circumstances described above. The National Medical Examiner will monitor the number of ME MCCDs being completed in all areas/medical examiner offices to ensure that ME MCCDs are used as intended and to identify variation in application of this approach by medical practitioners and stakeholders.

DHSC has published official guidance for completing MCCDs including ME MCCDs. Information about ME MCCDs was agreed by DHSC, the Ministry of Justice and the General Register Office. The referring medical practitioner (who has taken responsibility to ensure death certification is completed but does not fulfil the criteria to be the attending practitioner) and the referring coroner are required to be named on the ME MCCD.

The medical examiner role complements the established statutory child death review process and gives bereaved families an opportunity to raise concerns about care provided with someone not involved in providing healthcare for the deceased. Medical examiners ensure the appropriate notification of deaths to the coroner and support local learning by identifying cases and matters that should be considered through clinical governance arrangements, including the child death review process. The elements of medical examiner scrutiny are generic and the same for deaths of children and adults, as are the principles around timeliness of care and escalation of concerns. Medical examiners must ensure in all cases that they (or a medical examiner officer) offer the bereaved family an opportunity to ask questions or raise concerns, and the interaction with the attending practitioner is completed. The medical examiner must review the health records. Medical examiners should be alert to cultural and religious sensitivities around all deaths they review, including those of neonates and children.

Medical examiners should gain understanding of paediatric, neonatal and obstetric matters through experience and interaction with local colleagues, as they would for deaths in any specialty with which they are less familiar. The highly specialised nature of neonatal and paediatric care and the potential complexities that may arise when providing independent scrutiny of such deaths make it important for medical examiners to ensure their review and conclusions are informed by latest thinking and good practice. Medical examiners should seek opportunities for training in this area and when reviewing cases seek advice from subject matter experts. These may include paediatric specialists or medical examiners who work as paediatricians, always considering that such experts or their teams and close colleagues may have provided care for the deceased child.

The National Medical Examiner’s good practice paper describes the interaction between medical examiners and the child death review process. Medical examiners should work with treating teams to ensure deaths of all children under 18 years are notified to the relevant Child Death Overview Panel (CDOP) contact. Usually, deaths of children are reviewed by the CDOP covering the area in which the child lived, which may be different from where the child died. There should be good liaison between the medical examiner office and the CDOP co-ordinator. While child death review guidance suggests medical examiners should be involved in child death review meetings, this may not be feasible for the individual medical examiner as these meetings normally take place some weeks or months after the death. However, the medical examiner office should provide information to support the child death review process.

Requirements for completing the AP MCCD and ME MCCD are set out in the Medical Certificate of Cause of Death Regulations 2024 and government guidance but are summarised below and in the diagram that is available for download.

Medical examiners and officers can support and advise attending practitioners and coroners/coroner’s offices at all stages of this process. For attending practitioners, this includes advising on MCCD content before its completion and whether coroner notification is required. Most cases will be straightforward and follow the standard process described below. Other potential routes to registration and actions are also set out below and should be followed when appropriate.

The attending practitioner must review the deceased person’s health records to formulate the proposed cause of death. They then complete the AP MCCD and make it available to the medical examiner along with the deceased person’s relevant health records and any other relevant information.

Medical examiners must then make whatever enquiries they consider necessary. This involves a proportionate review of relevant patient records and consideration of any information provided to them or which they consider relevant. They must record their conclusions at this point.

The medical examiner (or the medical examiner officer acting on their behalf) and then interacts with the attending practitioner, which allows discussion of and refinement of the causes of death if appropriate. This interaction may be verbal or by correspondence. A record must be made of any discussions with the attending practitioner and the responses they give.

The medical examiner or the medical examiner officer acting on their behalf then offers an appropriate person the opportunity to ask questions about causes of death or raise concerns about care before death or the circumstances of death. Normally this will be a bereaved person, such as the deceased person’s next of kin. This interaction must be verbal (by telephone or face to face/video conference if desired and practical) unless there are exceptional reasons for using other means of communication. A record must be made of the discussion and its outcome.

The medical examiner office sends the completed AP MCCD to the registrar and the death must then be registered within 5 days.

If the medical examiner believes the attending practitioner’s proposed causes of death need to be revised, they (or the medical examiner officer acting on their behalf) should explain why to the attending practitioner and record their reasons and the interaction. The attending practitioner will need to send a new AP MCCD with revised causes of death. Refer to ‘What if the causes of death cannot be agreed?’ in section 2 if required.

Concerns may arise from reviewing the patient record or from the interaction with the attending practitioner or the bereaved person. Where they do, the medical examiner or the medical examiner officer acting on their behalf refers the case for review (more information in section 5).

If a representative of the deceased provides information that leads the registrar to believe the cause of death may need revision, the registrar must consult a medical examiner. The medical examiner must consider whether the causes of death need to be revised. If appropriate, they will liaise with the attending practitioner. The medical examiner office either needs:

a) to provide the attending practitioner with the information they received from the registrar and invite the attending practitioner to revise the causes of death, and inform the registrar of this invitation. New causes of death should be discussed with the bereaved person or representative of the deceased. Any new concerns about care detected should be referred for review (more information in section 5). The new AP MCCD with the revised causes of death should then be sent to the register office

b) to confirm to the registrar that the attending practitioner is not being invited to revise the causes of death in the AP MCCD and why

The requirement for coroner notification may become apparent at different stages, either to the attending practitioner or the medical examiner or officer. Attending practitioners will in some cases find it helpful to discuss with medical examiners and officers at the outset whether coroner notification is required. This supports consistent notification of deaths.

The coroner informs the medical examiner office of their decision and the medical examiner office informs the attending practitioner. The medical examiner does not provide independent scrutiny in these cases.

While medical practitioners may be required to notify coroners of deaths under the Notification of Deaths Regulations 2019, in many cases coroners decide that their duty to investigate is not engaged. In these cases, the coroner sends form CN1A to the attending practitioner and medical examiner office, with relevant information to facilitate completion of the AP MCCD.

In cases where no attending practitioner is available in a reasonable time and the cause of death is natural and known, a referring practitioner (not the medical examiner) may inform the coroner. The referring practitioner is the medical practitioner who has taken responsibility for ensuring the death is certified but cannot fulfil the criteria to be the attending practitioner. A senior coroner may then send form CN1B to the medical examiner office, requesting that a medical examiner completes a ME MCCD. ME MCCDs can only be used following referral by a coroner.

The medical examiner carries out a proportionate review of medical records. Medical examiners, supported by medical examiner officers, offer an appropriate person (usually a bereaved person, next of kin to the deceased or a representative of the deceased) the opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns. Any detected concerns about care should be referred for review (more information in section 5).

The ME MCCD is then sent to the register office and the death must be registered within 5 days.

In circumstances where the medical examiner’s enquiries indicate that coroner notification is required or the medical examiner concludes that they are unable to establish the cause of death, the case can be referred back to the coroner.

Further information is available at the following web pages:

In England:

National Medical Examiner’s office: nme@nhs.net

In Wales:

The medical examiner office at our trust has been commissioned by NHS England to appoint medical examiners to carry out independent scrutiny of the causes of death for non-coronial deaths of patients previously registered under your care.

Our medical examiner office will require access to information relating to relevant patients, their next of kin and the medical practitioner (known as the attending practitioner) completing the Attending Practitioner’s Medical Certificate of Cause of Death (AP MCCD).

This statement describes the information governance arrangements in place to facilitate this.

The statutory duties of medical examiners, their appointing trusts and attending practitioners are set out the regulations.

Attending practitioners are under a statutory duty to:

Medical examiners, upon receiving the AP MCCD from the attending practitioner, are under a statutory duty to:

Both attending practitioners and medical examiners are under a statutory duty to refer the death to the coroner, if they are unable to establish or confirm the cause of death.

For both attending practitioners and our medical examiner to undertake their statutory duties, our medical examiner office will require access to:

The Access to Health Records Act 1990 (AHRA) has been amended to establish the statutory right of medical examiners to access health records. Under the Coroners and Justice Act 2009 (Commencement No. 22) Order 2024 (paragraph 3n), from 9 September 2024 medical examiners were added to the list of people who can apply for access to a health record (schedule 21 paragraph 29).

A “health record” means a record that:

Where a medical examiner (via the medical examiner office) applies for access to health records, you are obliged to give them access to the record. In most cases you will be required to provide a copy of the records, but the medical examiner may also require you to allow inspection of the records.

The usual timescales for compliance with requests under AHRA have not changed, however you are expected to respond promptly to ensure that both attending practitioners and medical examiners can fulfil their statutory duties without delay.

The usual exemptions from access under AHRA (for example, where the record includes a note, made at the patient’s request, that they did not wish access to be given on such an application) have also not changed. However, such exemptions are highly unlikely to apply in respect of an application by a medical examiner. In the rare event that you consider an exemption may apply, you should contact the medical examiner office immediately. If a medical examiner cannot access relevant information to complete scrutiny, they will have to refer the case to a coroner. Notifications to the coroner caused by such cases should be avoided wherever possible, and all parties should work cooperatively to avoid unnecessary distress and delay to bereaved people.

The UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA) only apply to information relating to living individuals.

Information relating to deceased patients does not constitute personal data and therefore is not subject to data protection law.

Information relating to living next of kin and healthcare professionals is personal data and is subject to data protection law.

The main lawful basis for sharing such personal data is “public task” (Article 6.1(e) UK GDPR). This says you may process personal data where this is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority. This includes the exercise of a function conferred on a person by an enactment or rule of law. In this case, the processing of personal data is necessary for both the attending practitioner and medical examiner to undertake their statutory duties (see above).

For personal data held within health records, the lawful basis is also “legal obligation” (Article 6.1(c) UK GDPR). This says you may process personal data where this is necessary for compliance with a legal obligation to which you are subject. In this case the relevant legal obligation is to provide access under the AHRA.

Typically we do not require access to special categories of personal data.

The common law duty of confidentiality continues beyond a patient’s death.

You may share confidential information where disclosure is required by law. In this case, disclosure of the deceased patient’s health records, including confidential information within them, is required by law under the legislation referred to above, including the AHRA.

Delays in scrutinising and certifying deaths can contribute to the distress of bereaved people.